The Hidden Cost of Efficient Learning

Why Active Learning Matters More in an Age of Digital Media and Generative AI

Teachers are seeing polished essays that students cannot explain. Parents watch children complete assignments in minutes, yet struggle to articulate their thinking. The work looks finished, but learning feels hollow. Policymakers worry about equity, ethics, and what gets lost when efficiency becomes the priority.

Researchers warn that while AI can increase efficiency, it may also reduce the very cognitive effort that learning depends on. The problem is not that students are lazy, unmotivated, or incapable of thinking deeply. The problem is that many digital learning environments change expectations about what learning feels like, and, in doing so, reshape how learners engage with it.

Learning Was Never Meant to Be Passive

For years, education treated students like empty vessels to be filled (behaviorism). But theorists like Piaget argued that we don't just absorb knowledge; we construct it. Learners don’t simply take knowledge in; they build it by testing ideas, encountering contradictions, and reorganizing their thinking.

From this perspective, learning depends on disequilibrium, the experience of realizing that what you currently understand is no longer sufficient. This cognitive tension can feel uncomfortable, but it is not a flaw in the process; it is the engine that drives it.

When new information fits easily with what we already believe, we assimilate it. Learning feels smooth. But when it doesn’t fit, accommodation is required. Understanding must change. That process is effortful, slow, and uncomfortable.

In other words, active learning assumes that learners play a role in their own learning. They question, struggle, revise, and persist. In this model of learning, curiosity and critical thinking are central to how learning happens.

Digital Media and AI Default Toward Passive Learning

Digital tools and AI aren’t necessarily designed to undermine active learning. But many of their core design features unintentionally do so. For example, most digital platforms are optimized for speed, clarity, and completion.

In this model, confusion is treated as a problem to fix, rather than an essential part of the learning process. Frustration is minimized. Answers arrive immediately. Progress is measured by finishing rather than transforming understanding.

These features of digital media and AI are incredibly effective for access and convenience. They are less effective for learning that requires exploration, uncertainty, and revision.

When a learner encounters difficulty, AI resolves it almost instantly. Explanations are fluent, organized, and confident. The system restores a sense of clarity before the learner has had to grapple with the mismatch or disequilibrium that would have motivated deeper understanding.

Over time, this subtly trains a passive learning stance:

uncertainty becomes something to avoid

curiosity feels unnecessary

effort feels inefficient

struggle feels like failure

This helps explain why students may appear engaged but struggle to explain their thinking, why work looks polished but understanding is thin, and why confidence collapses when support is removed.

The issue isn’t the tool. It’s the learning approach the environment encourages.

Why Curiosity and Critical Thinking Take the Hit

Curiosity thrives when learners are allowed to linger in questions. Critical thinking requires time, cognitive space, and tolerance for ambiguity.

Digital environments, and especially AI-supported ones, often remove those conditions.

When confusion disappears quickly, learners have fewer opportunities to ask:

Why doesn’t this make sense yet?

What am I missing?

How does this connect to what I already know?

Instead, learning becomes something that happens to students rather than something they actively do.

This aligns with what many parents and teachers report: students are completing tasks quickly but struggling to reason, explain, or transfer knowledge. From a developmental perspective, this is not surprising. Critical thinking isn’t simply a skill to be practiced; it’s a cognitive state that requires attention, emotional regulation, and the willingness to stay with uncertainty.

When environments consistently reward fast resolution, the brain learns to escape discomfort rather than engage with it.

A Concrete Example

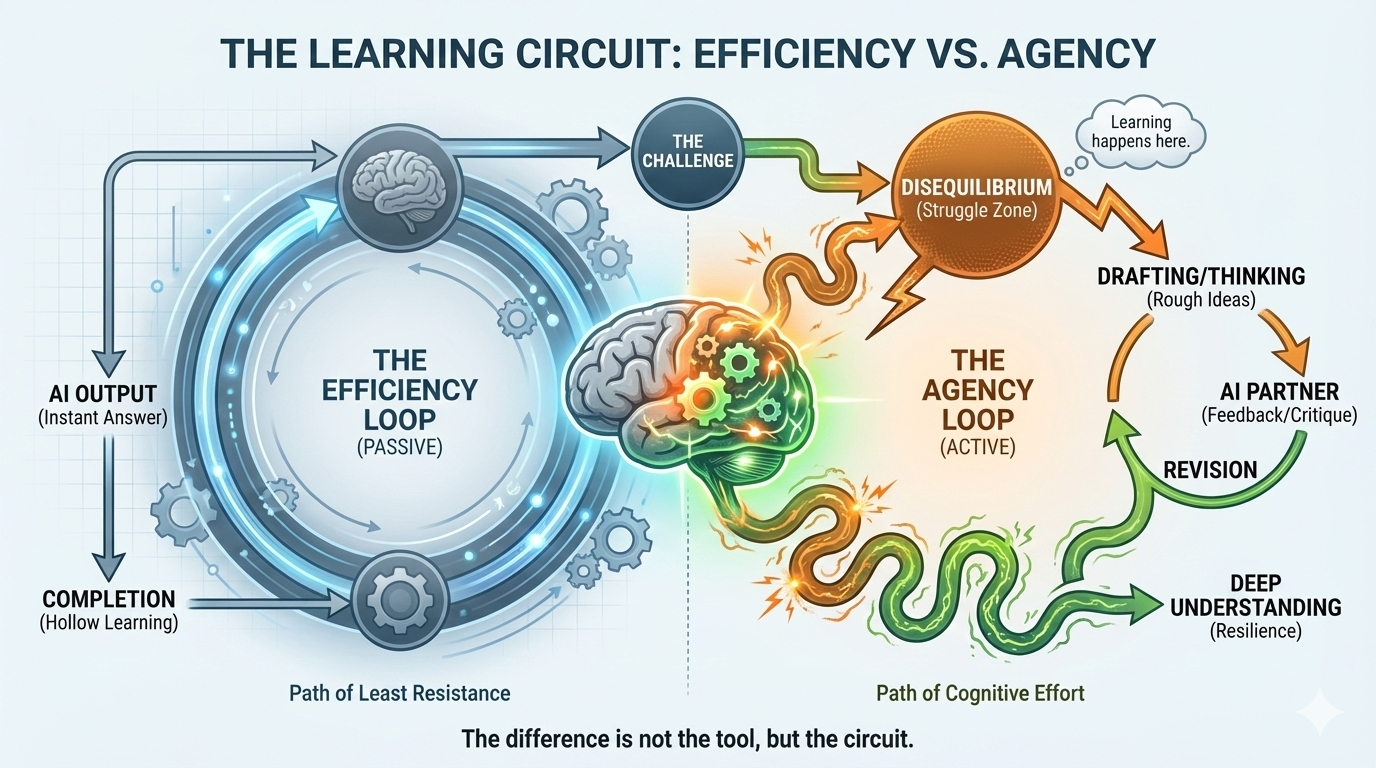

Consider a student writing an essay or solving a complex problem. The outcome depends entirely on the loop they choose.

🔴 The Passive Loop

Optimized for speed and completion.

Immediate Input: The student inputs the prompt into AI immediately.

External Thinking: The tool generates the outline, arguments, and structure.

Frictionless Edit: The student polishes the language without grappling with the logic.

Outcome: The work looks finished, but the learning is hollow. The student struggles to answer follow-up questions.

🟢 The Active Loop

Optimized for curiosity and retention.

The Pause: The student sketches ideas or attempts a first draft before opening any tools.

Productive Struggle: The student encounters "disequilibrium" (confusion) and tries to resolve it manually.

AI as Partner: AI is brought in late to ask: "What did I miss?" or "Critique my argument."

Outcome: The process is slower, but the knowledge belongs to the student. They can explain and defend their thinking.

While the Efficiency Loop prioritizes speed, the Agency Loop prioritizes understanding.

The same pattern appears in mathematics. A student asks ChatGPT how to solve for x. The tool shows the steps. The student copies them. But when the equation changes slightly, they're lost, because they never wrestled with why those steps work.

In an active learning loop, the student struggles first. They sketch ideas, encounter contradictions, feel uncertain, and revise. AI may still be used, but later, to challenge assumptions, generate counterarguments, or test clarity.

The difference is not whether AI is used. The difference is when and how it enters the learning process.

What to Do Instead: Restoring Active Learning in a Digital Age

If the problem is not learners’ capacity, but the conditions surrounding learning, then the response is not to remove technology. It is to design learning experiences that restore agency, curiosity, and productive struggle, while using digital media and AI in ways that support, rather than replace, the work of thinking.

Here are practical ways parents and teachers can do that.

Use AI to Extend Thinking, Not Replace It

AI is most powerful when it enters after thinking has begun, not before it has started.

What this can look like in practice:

Write first, AI second. Ask students to write an explanation, solution, or argument in their own words first.

Gatekeep the tool. Only then invite AI into the process.

What this avoids:

Zero-draft generation: Asking AI to generate the answer from scratch.

Uncritical acceptance. Treating AI output as finished understanding.

Helpful AI prompts that support active learning:

“What assumptions might I be making here?”

“What’s a reasonable counterargument to my position?”

“Where might my explanation be unclear or oversimplified?”

“What would someone who disagrees with me say?”

Used this way, AI becomes a thinking partner that challenges, stretches, and refines ideas rather than replacing the work of construction.

Slow the Moment of Resolution

Digital tools are excellent at resolving confusion quickly. Active learning often requires the opposite. When a learner is confused, resist the impulse to immediately clarify, search, or generate an answer.

What this can look like in practice:

Articulate the confusion. Before Googling or asking AI, ask the learner to write or say what doesn’t make sense yet.

Implement a waiting period. Encourage a short pause: “Let’s sit with this for two minutes before we look anything up.”

How digital tools can help (without short-circuiting learning):

Create a ‘confusion log’. Use a notes app or shared doc where students record “what I think so far” and “what’s confusing me” before seeking help.

Pinpoint the friction. Have students highlight or comment on the exact sentence, graph, or idea that triggered confusion before moving on.

This keeps disequilibrium alive long enough to motivate deeper thinking instead of erasing it immediately.

Make Curiosity the Goal, Not Just the Outcome

AI-mediated learning often rewards completion. Active learning rewards inquiry. Shift attention toward the quality of questions learners are asking, not just the answers they produce.

What this can look like in practice:

Reward high-quality inquiry. Praise questions like: “Why does this work here but not there?” or “What would happen if…?”

Require a lingering question. Ask learners to submit one open question along with completed work.

How digital tools can help:

Maintain a ‘parking lot’. Use shared documents, discussion boards, or classroom platforms to maintain a running list of “questions we’re still thinking about.”

Track the evolution. Encourage students to revisit and revise questions over time as their understanding grows.

This teaches learners that curiosity is not a detour from learning; it is learning.

Make Struggle Visible

Many learners interpret difficulty as failure because learning environments rarely name struggle as part of the process. Adults can change this by narrating the learning process out loud and making the invisible work of thinking more visible.

What this can sound like:

“This is usually the part where people feel stuck.”

“If this feels uncomfortable, it often means your thinking is changing.”

“This confusion is doing important work.”

Why this matters in digital environments:

When AI or digital tools make learning feel smooth and immediate, students may assume struggle signals incompetence. Naming struggle reframes it as evidence of growth rather than deficiency.

How digital tools can help:

Capture the messy middle. Use shared documents or learning platforms to capture drafts, revisions, and false starts, not just final products.

Self-annotate the struggle. Encourage students to annotate their own work with comments like “This part felt confusing” or “I changed my mind here.”

Review version history. Use version history or screen recordings to show how ideas evolve over time, making the struggle visible rather than hidden.

Use AI as a mirror. Ask students to use AI reflectively by asking it to identify where an explanation might still be unclear, reinforcing that learning is iterative.

When struggle is documented and preserved rather than edited out and erased, learners begin to see it as a normal and necessary part of learning rather than something to avoid.

Interrupt Avoidance Gently

When learners disengage at the first sign of difficulty, the goal is persistence, not pressure.

What this can look like in practice:

“Explain it one more time in your own words before checking.”

“Try one more example before we bring in support.”

“What’s one small step you could take next?”

How digital tools can support this:

Allow ‘rough’ formats. Use voice notes, screen recordings, or drafts so learners can externalize partial thinking without needing a polished answer.

Assign iterative milestones. Encourage iterative submissions rather than one final product.

Small moments of persistence rebuild tolerance for effort over time.

Protect Unfinished Learning

Digital environments push toward closure, but learning often benefits from leaving ideas open.

What this can look like in practice:

Circle back. Revisit an earlier misconception weeks later and ask, “How do you think about this now?”

Leave loose ends. End discussions with: “What are we still unsure about?”

How digital tools can help:

Map the journey. Maintain evolving notes, timelines, or concept maps that show how understanding changes over time.

Visualize the progress. Use version history or saved drafts to make learning visible, not just final answers.

This teaches learners that learning unfolds gradually and that not knowing yet is a legitimate, productive state.

From Efficiency to Agency

None of these practices rejects digital media or AI. They reposition them.

They shift technology from:

answer provider → thinking partner

efficiency engine → reflection tool

clarity machine → curiosity amplifier

When learners are supported in staying with uncertainty, asking better questions, and using tools to extend, and not to replace their thinking, active learning becomes possible again, even in technology-rich environments.

Keeping Humans in the Learning Loop

Digital media and AI can support learning, but only when humans remain actively involved. Teachers, parents, and learners themselves provide something technology cannot: context, judgment, and relational feedback.

Active learning depends on agency. Curiosity depends on permission to not know yet. Critical thinking depends on time and cognitive space.

When we restore those conditions, learning regains its depth, not by rejecting technology, but by using it in ways that preserve the work of thinking.

This approach requires intention. It means designing learning experiences that feel slower and messier than what AI makes possible. But when we do this work, and when we keep humans actively engaged in the learning loop, we preserve not only knowledge acquisition but the curiosity, agency, and resilience that make lifelong learning possible.